In this regular feature, we take a closer look at the workspace of people who inspire us. Here Imogen Davis and Ivan Tisdall-Downes tell us about how urban foraging informs their menu. Photographs by Harriet Clare

Together, Imogen Davis and Ivan Tisdall-Downes run Native, the restaurant in London Bridge which specialises in wild food from the British Isles. They hit the headlines last year when they first put squirrel on the menu but as food waste becomes a bigger and bigger issue, they have been justified in using such ingredients.

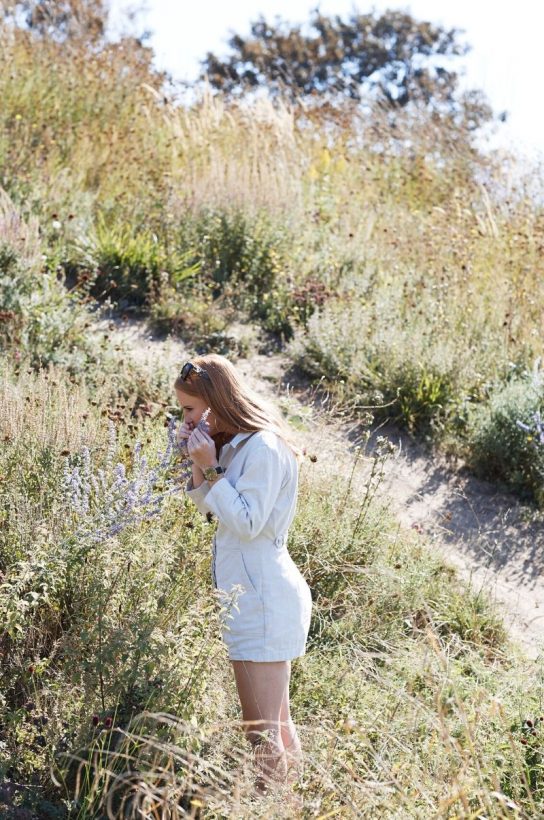

Many of the dishes that chef Tisdall-Downes creates use foraged ingredients – that both he and Davis, who runs front of house, source themselves or from trusted suppliers. The pair often use Mondays, when the restaurant is usually closed, to go out looking for new and familiar plant species to work with.

They took CODE not to a forest or a coastal meadow, but to Burgess Hill in Camberwell. It didn’t sound very promising … but sure enough, there were plenty of edible ingredients if you knew where to look. Foraging doesn’t require a great deal of special equipment – a keen eye and a breadth of knowledge are, however, essential.

Sight

Imogen Davis: My aim is that one day on my train journey into work [from Wimbledon to London Bridge] I’m going to be able to identify everything I go past! There are still so many different things that pop up and I’m like “I’ve never even seen that before”.

Then my next thought is, “is it edible, or not edible”? It’s just exciting because it’s a whole different world. When everything’s so busy it’s really refreshing to be open – you can’t force anything and whatever you find on the day is what you find. So it’s nice that we bring a little bit of that back into the restaurant … Yes we’ve got to serve people dinner, but we let the land dictate, which means we’ve got to be a little bit creative and flexible – and have fun with it, because ultimately that’s what food should be.

Ivan Tisdall-Downes: We try and keep a skeleton structure to the menu for a month and then chop and change according to what we find. So, herb garnishes depend on what we find, meat on what the game keeper shoots and so on. Sometimes we are fighting the birds off, sometimes we have something that will be on the menu for one day only and that’s it until next year.

We try to let the suppliers dictate what’s going to be on the menu – instead of phoning them up and saying “we want this many courgettes…” we ask them what they’ve got. We work quite closely with Sutton Farm – they email us and tells what they have and we put it on the menu. It’s a nice way to work.

In addition, you have to have trust in the chefs but they’ve all been with us for two years, pretty much, which is quite a long time. Jasper my sous chef, and my brother, are in the kitchen today. He’s been with us for two years.

Over there is some mallow, which is on the menu at the moment – we make a velouté out of the leaves, a green sauce, and then we garnish with the flowers. It has something in it which makes you salivate and it thickens sauces really well.

Touch

ID: When we see something we’re not sure about, we use the known warning sights, the particular identifications – these are often touch. Wild carrot is a lot like hemlock and the way to tell is whether it’s got a smooth or a hairy stem. Hemlock grows to be really tall, over 8ft, but it’s also known as Queen Anne’s Lace and the way that you identify it… I was once told that the way to know it’s safe and wild carrot is that Queen Anne has hairy legs so if you feel the stem and its hairy then you know it’s safe to eat.

This is wild carrot because it’s got really spiky hairs. [Ivan looks slightly less confident – hemlock is deadly.] Ivan grew up in the city but I grew up in the country, so I’m often like ‘yeah, you’ll be fine!” IT: I just realised this is a type of mint. The best test is to know if it’s a member of the mint family is if you roll the stem between your fingers and it’s square, then 90 per cent of the time it’s in the family [ID: that doesn’t always mean it’s edible!] and then the leaves grow in pairs opposite each other – same as most mints. You can also smell and taste it.

ID: I’ve just found greater plantain, which is brilliant. It’s not related to actual plantain – the leaves have really thick veins – but they are really good leaves to use in a salad, they add moisture. In fact, they use extract of greater plantain in loads of expensive hand creams – if you rub the leaves between your hands, it releases so much ‘juice’; makes them feel really smooth!

Taste

ID: This tiny patch is right in the centre of a very busy area and even here you’ve got little rosehips, yarrow, nettles, mustard, there’s the mint, beech leaves, mallow, greater plantain. If you know what to do with them it’s actually really fun – there are so many healing properties too, I think we need to go a little bit more towards eating from the land and relying a little bit more in things like elderberries. They have started selling bottles of elderberry tonic for £13 as a flu preventative. But you can just go and pick them!

We’ve now got all these amazing herbs so we can make our own teas – a yarrow tea, yarrow kombucha. We can use cornflowers, loads of different foraged leaf teas and they taste amazing. We’re also making hay kombucha, which is really tasty. IT: we’ve got pine cone kombucha, and we’ve started appleweed as well. Yarrow was originally used to make beer by monks. Let’s pick up these rosehips, they are great for making jelly. They have hairs inside so they’re not great to eat – they don’t do your insides any good. But they’re super high in vitamin C – one of the highest. Once I made a loaf of bread with rosehips and I had to cut them in half and peel them. It took me absolutely ages.

There’s loads of Jerusalem artichoke plants here. When I worked at Blue Hill Farm we used to pick the flowers, dust them in pea flour and deep fry them. I used to have to spend the mornings picking sunflower heads when I worked there too. It wasn’t the worst job in the world – September is the season for sunflowers, sunchokes and Jerusalem artichokes.

ID: We are firm believers in ‘what grows together goes together’. We try and taste like that. Because we didn’t train in the industry – everything we do is by taste so it’s not that we were taught what goes together, we just try it and see if it works. And that’s where it can be quite liberating, not the same as other people. We can’t do it any other way.

Weeds and seeds

ID: It’s amazing that seeds have found their way here from all over the world, brought from birds or on people’s shoes and so on; now they’re self-seeding. It’s just amazing that we can now find all this produce, it’s really exciting. There are so many non-native ingredients growing everywhere and they do well here. When we talk about weeds… we need to harvest and eat them, like Japanese knotweed.

We’re doing our invasive species dinners, teaming up with different chefs for Monday nights.

Olia Hercules, for instance, is doing crayfish, which is an invasive species. On other guest chef menus there’s hogweed, knotweed…

IT: Alexanders are an invasive species too, they’re all over Kent – you can eat all parts of them and because they grow everywhere, you can gorge on them!

Jars

ID: We harvest things when they’re in season and then pickle them and so on. It’s how we survive. If sometimes we only want the young shoots, or the older shoots, or flowers – you have to remember what’s what.

IT: it’s nice now because we’re still superyoung as a business [ID and age wise!] but we are getting to the stage where now we can start to use our pickles from the year before. We’ve got the time and with Native at London Bridge, we’ve got the space. We are learning that we have to preserve for January now, when we have artichokes, beetroot and carrots and not much else; so now we think forward for what we can ferment and preserve. Nice evolution of the menu in ways that we haven’t done in previous years.

Extras

IT: We couldn’t do foraging without our phones. We use an app (and books) to help identify plants, and also to photograph what we’ve found, in case we’re not sure, or want a reference. What we’re really bad at is remembering where we’ve found things! ID: I’ve brought my little foraging knife which is really useful for digging down to be able to pull up a plant by the root, and it has a brush for cleaning mushrooms too. Useful particularly at this time of year.

For more long reads delivered straight to your door, subscribe to the Quarterly here